The conventional market wisdom suggests that the bonds usually lead the change in market cycles. Traditionally traders have closely followed the yield curve shape, benchmark (10 year) yields and high yield credit spreads to speculate the near term moves in equity, currency and commodity markets. Two simple reasons for this traditional practice are –

(i) Bond markets are usually more correlated with the economy.

(ii) Size of bond markets is materially larger than the equity, currency and commodity markets. It has the largest number of leveraged positions at any given point in time; and most of the large and influential market participants are more active in bond markets as compared to the other markets.

I am however inclined to disregard this piece of conventional wisdom. In my view, it would make sense only if the markets are operating in a free and fair manner. In cases where the central bankers and governments (through Sovereign Wealth Funds and other institutions controlled by it) actively and frequently intervene in the market, effectiveness of bond markets in leading the markets is impaired.

The world has definitely changed after the global financial crisis (GFC 2008-09). Central bankers, government, and public institutions are now playing significantly more active roles in the financial and commodity (especially gold and energy) markets. Bond prices are often influenced to suit the objectives of fiscal policy. Stock prices are influenced to suit political expediency.

Even pre-GFC, equity and bond traders did look at proxies like USD/CHF or copper—known as "Dr. Copper" for its economic sensitivity—for directional cues. In the past one decade we have seen Japan’s central bank buying equities; India’s government nudging markets via state-owned entities like LIC; the US Fed’s quantitative easing indirectly supporting massive amounts of stock buybacks; and Sovereign wealth funds in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries piling into equities. This clearly indicates that in markets "no fixed formula works forever." Markets are adaptive. What held true for the past 35 years might not hold for the next 35.

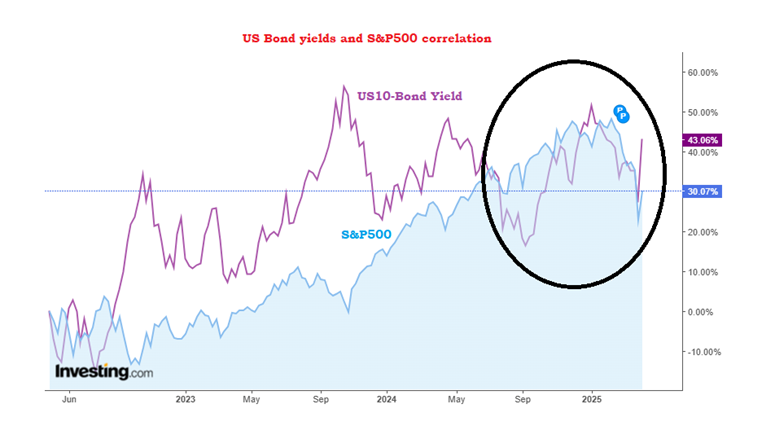

US Bond yields no longer a lead indicator

In my view, the yield curve is fully relevant only if the market is free and genuine demand supply equilibrium of bond prices is discovered by the market forces. In situations where central bankers direct, manipulate or regulate yields, the yield curve is materially less important.

There is plenty of recent evidence, pointing that the US bond yields are no longer a strong indicator of the economy and/or markets. For example, consider the case of the US yield curve inversion in 2022-23.

Typically, an inverted yield curve—where short-term Treasury yields exceed long-term ones—has been a reliable harbinger of recession, preceding every U.S. downturn since the 1950s with a lag of roughly 6 to 18 months. The inversion that began in July 2022, peaking in mid-2023 with the 10-year/2-year spread hitting around -100 basis points, was the longest on record, lasting over two years. By historical standards, a recession should’ve hit by mid-to-late 2024. However, it has not happened; and the GDP growth held steady at 2.8% annualized in Q4 2024, and unemployment remains low at 4.1% as of March 2025.

Moreover, after un-inverting in September 2024—when the 2-year yield (around 3.6%) briefly dipped below the 10-year (around 3.8%)—yields have climbed across the board in the last two weeks. This morning, the 10-year yield is hovering near 4.5%, up from 4.0% in late March, while the 2-year has risen from 4.1% to about 4.5%. Incidentally, this rise coincides with a spike in recession odds, with the New York Fed’s yield curve model pegging the probability of a recession by mid-2026 at around 40%, up sharply from 25% a month ago. Normally, you’d expect yields to fall as recession fears mount, reflecting a flight to safety and anticipation of Fed rate cuts.

Prima facie, it appears that the bond market is more concerned about the rising inflationary expectations, particularly in light of the latest tariff policy of the US government. CPI is currently running above 3%—and there is skepticism about the Fed’s willingness to cut rates meaningfully from their current 4.75%-5.0% range. Higher yields also reflect a demand for more compensation amid uncertainty which could stoke inflation further. Arguably, the economy’s resilience—strong consumer spending, a robust labor market—may have also impaired the yield curve’s predictive edge this time. Structural shifts, like massive Fed balance sheet expansion since 2008 or global demand for long-term Treasuries, have certainly distorted its signal.

The recent yield rise despite recession odds implies that bond traders are betting on tighter policy or inflation risks, despite economic data flashing slowdown warnings (e.g., manufacturing PMI below 50 for months).

Conclusion: The yield curve’s relevance erodes when it’s less about market discovery and more about central bank glide path. Though it’s still worth watching, it’s no longer the king it once was in a freer market.

Tomorrow I will share my thoughts of what could be a better indicator, or aa mix of indicators to assess the likely market direction.

No comments:

Post a Comment